I went into Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere with the benefit of knowing what it was really about. No, this is not the rousing Bruce Springsteen career retrospective that many might be expecting. Instead, it chooses to adapt Warren Zanes’ book, “Deliver Me From Nowhere: The Making of Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska” and just cover the brief period in Bruce’s career during which he wrote and recorded the album “Nebraska”. Music biopics have had a boom in the last few years with movies like Bohemian Rhapsody, Rocketman, Straight Outta Compton, Elvis, Respect, Whitney Houston: I Wanna Dance with Somebody, Bob Marley: One Love, Back to Black, and more. But as this wave starts to die down, a new trend seems to be emerging. I’m calling it the micro-biopic. These are not your cradle-to-grave biographies. The micro-biopic is a snapshot of a short period of time in a famous figure’s life. We just saw this with The Smashing Machine and with, an even closer comp to Springsteen, A Complete Unknown, which mainly focused on Bob Dylan’s pivot from folk to electric. Similarly, in this film, Springsteen makes a career-threatening genre shift from rock/pop to folk. Knowing the small scope the movie would cover had me concerned it would be light on story and high on performance. Not only did that turn out to be true, but that also wasn’t my only issue with the film. There are definitely interesting threads inside this real-life story, but Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere either chooses not to explore them or does so in such a blunt way it renders them flat.

In 1982, Bruce Springsteen released his album “Nebraska”. It came between the 1980 double album “The River” and his boost to superstardom in 1984 with “Born in the U.S.A.” “Nebraska” was different from the rest of Bruce’s discography in every possible way. The sound was lo-fi, acoustic, recorded at home without the E Street Band. The themes were dark, inspired by the work of Flannery O’Connor, Terrence Malick’s 1973 film Badlands, and his own childhood trauma. The film opens with a flashback of young Bruce and gives us a peek at the Springsteen family life. His father (Stephen Graham) was drunk and sometimes abusive and his mother (Gaby Hoffmann) was silently resigned to her husband’s behavior. We return to glimpses of Bruce’s past throughout the film, but our contemporary story starts at the end of Bruce’s 12-month River Tour. Looking for some quiet post-tour downtime, he rents a secluded house in Colts Neck, New Jersey. But the comedown after a blockbuster tour is hard to handle. And the Bruce that’s returning home to New Jersey isn’t the same one that left. He’s a burgeoning star now and no longer fits into the world he once knew. He visits old haunts like the Stone Pony in Asbury Park and drives by his childhood home. He even strikes up a romance with single-parent Faye Romano (Odessa Young playing a composite character of Bruce’s real-life love interests) that fizzles out when he’s unable to connect and commit. All of this just leaves him feeling more alone and estranged and haunted by the unresolved trauma of his past. 32 and feeling lost, Bruce decides to take these feelings and channel them into new music. We see him writing lyrics, recording demos in his bedroom at the Colts Neck house with guitar tech Mike Batlan (Paul Walter Hauser), and pleading with his manager Jon Landau (Jeremy Strong) to get everyone around them on board with Bruce’s singular vision for the album. In the end, we’re left with Bruce’s most personal album and a very depressed man teetering on the edge of a breakdown.

I was surprised how much this movie ended up being about mental health. Bruce is quite literally haunted by his past. Coming back to his hometown, dealing with the overwhelming silence and adrenaline crash after life on tour, trying to adjust back to normal life, and being confronted face-to-face with people and places he used to know. He’s seeing ghosts. Bruce’s flashbacks become increasingly more real and immersive. We also learn mental health issues run in his family and he begins to worry that it is in his DNA. He tried for so long to push that aside with his unresolved trauma but it becomes impossible to ignore. He says towards the end of the film, “I don’t think I can outrun this anymore.” While likely true to Bruce’s experience and of many who struggle with mental health, at the end of the day, a movie about depression isn’t exactly fun to watch. And for a musician so well-known for his charisma, it’s kind of disappointing to see him portrayed only as solemn and tormented. I’m not saying Bruce as a person and as a character in this film shouldn’t have any depth. Of course not. We want to see complex characters with layers. But there needs to be some balance. Especially when he is a real person with a famous persona we barely get any glimpses of in the film. Ultimately, the movie ends up being more about depression than it is about Bruce Springsteen.

The film’s flashbacks serve a storytelling purpose, but they just didn’t work for me. The story goes back to them too many times and the scenes felt way too heavy-handed. Especially because they were rendered in black and white. Director Scott Cooper shared with Rolling Stone that Bruce told him he remembers those moments of his childhood in black and white so that’s why they’re depicted that way in the movie. Evidently, Bruce was very involved in writing the script and crafting the film. It is his story afterall. Bruce also told Variety that he allowed the movie to explore his darker side, “because I’m old and I don’t give a fuck now.” All power to him for being so open and vulnerable. And who am I to argue with his experiences and the way he wants to communicate them? But, if I can argue slightly, I think that’s where there is something to be said about the separation of the subject and the art. Just because that’s how Bruce sees it in his head, doesn’t necessarily mean it makes for compelling and effective filmmaking choices. The heavy-handedness of the film is an issue I had throughout. There are multiple scenes where Jeremy Strong as Jon Landau basically just monologues to his wife psychoanalyzing Bruce and the songs he’s creating for “Nebraska”. It’s not even a conversation because his wife doesn’t speak. It felt like the filmmakers were treating the audience like they’re dumb and just straight up telling us what was going on inside Bruce’s head. One of the trailers for the film used dialogue from one of these monologues with Jeremy Strong saying, “When Bruce was little, he had a hole in the floor of his bedroom. A floor that’s supposed to be solid, he’s supposed to be able to stand on. Bruce didn’t have that. Bruce is a repairman. What he’s doing with this album is, he’s repairing that hole in his floor. Repairing that hole in himself. Once he’s done that, he’s going to repair the entire world.” The quote received such backlash for the same reasons I disliked these moments, that it was removed from the film before the release. If you are successful at telling the story, you shouldn’t have to spell it out for us like that. We should be able to understand what we need to know without being hit over the head with it.

The movie focuses so intently on the interiority of Bruce, it doesn’t give enough context for the outside world to tell us why this story matters in music history. In Warren Zanes’ book, he posits the thesis that Bruce Springsteen making “Nebraska” is the biggest left turn in pop music history. I didn’t get that at all from the movie. Once again, like Dylan going electric, Bruce was going folk. Right when he was about to break big, when he had surefire hits like “Born in the U.S.A.” in his back pocket, he chose to go in an entirely different direction. Zanes also called the album a turning point in music recording history. The process of a stripped-down collection of demos released more or less as it was, imperfections and all, was revolutionary. Now, artists release demos as bonus content (*cough cough* Taylor Swift), but this was new ground broken to achieve Bruce’s artistic vision (a smaller point of the film: always trust an artist and their vision). The movie doesn’t do nearly enough to contextualize how pivotal this moment was in the music world. We do see some moments of recording engineers and music execs pushing back on Bruce’s requests. Particularly his insistence that the album be released with no radio edits, no singles, no press, and no tour. “I don’t even want to be on the cover,” he tells Landau. “No tour, no press, no publicity. Just the album”. (Obviously my first thought was, “There will be no further explanation. There will just be reputation.” – Taylor Swift in 2017 signifying that rather than relying on interviews or statements, her album “reputation” would speak for itself). But these brief glimpses don’t convey the impact the recording and release of “Nebraska” had on the music industry, the world, and generations of musicians to come.

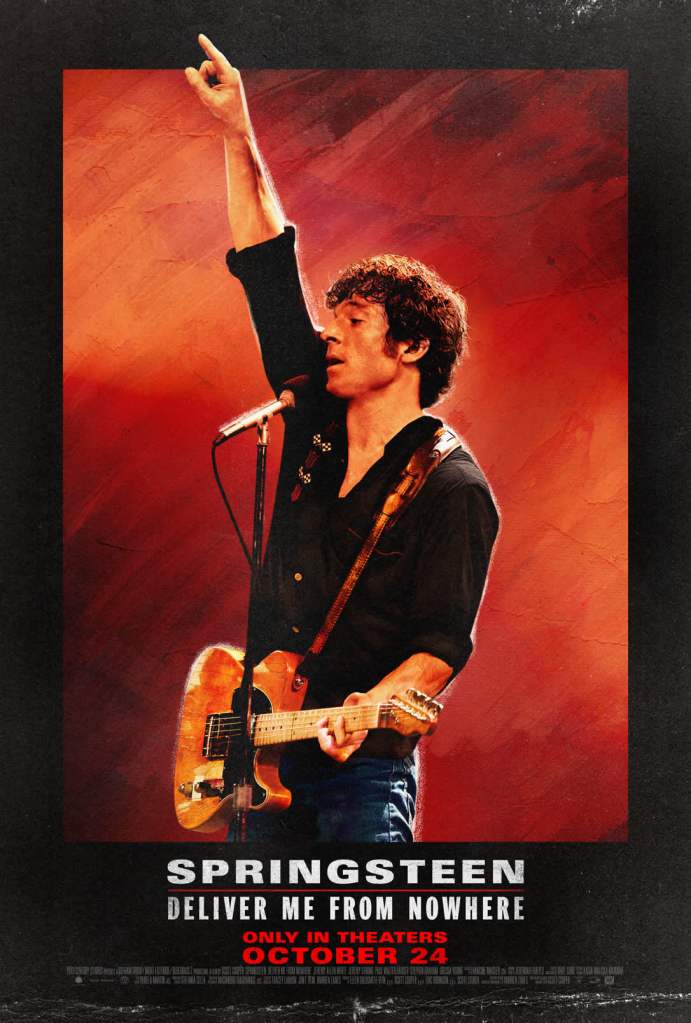

Jeremy Allen White’s performance as Bruce has always been the main talking point of the film. And he is great. He told Variety that when he was thinking about doing the movie, he warned director Scott Cooper that he didn’t know how to sing or play the guitar. But he spent months learning and he does do his own singing in the film (occasionally his vocals are mixed with Bruce’s). The moments where he gets to go full Bruce performance mode onstage performing “Born to Run” or recording “Born in the U.S.A.” are incredibly impressive. But while his more introspective, troubled moments as Bruce are believable and affecting, it’s not anything novel from him. We’ve seen White play brooding interiority for years now as Carmy on The Bear. He’s obviously good at it but that aspect of performance doesn’t give any new dimension to his career. He also just doesn’t disappear into Bruce the way Timothée Chalamet disappeared into Bob Dylan. In A Complete Unknown, I forgot I was watching Timothée Chalamet on screen. But in Deliver Me From Nowhere, I still saw Jeremy Allen White the whole time. I honestly don’t know if that’s because of his performance or the movie or my relationship to him as a celebrity or what, but I did find it notable. Jeremy Strong gets to play the rare nice music manager in a music biopic. He’s a real ride or die for Bruce. More than a manager, he’s a true friend, a rock, a support system. Jeremy Strong is a fantastic actor but his performance felt unremarkable, never quite elevating the material.

I’m sure if you are a passionate fan of the album “Nebraska”, this movie will have a lot to offer you. But, for me, the most exciting parts were unrelated to the album. As a Jersey native, I loved seeing all the Asbury Park locations that I’ve been to like the Stone Pony, the boardwalk, Frank’s diner, and more. The house Bruce rents in Colts Neck is also stunning. The music throughout the film when songs from other Springsteen albums are used as part of the soundtrack (“Hungry Heart”, “I’m on Fire”, “Glory Days”) remind us of the absolute rockstar he really is, even if we aren’t always seeing it onscreen. Even in a bad biopic, you are usually guaranteed good music. And I left the theater itching to listen to those songs rather than anything from “Nebraska”. The film is also beautiful to look at, with a vintage grain that feels authentic. Movies about depression aren’t fun, but they can be interesting. They can have something to say. One of the great American musicians took a career-defining gamble on a soul-searching album about his mental health and unresolved childhood trauma and it upended the music industry. That’s fascinating! So why is the movie about it so boring?

2025 Count: 70 movies, 43 seasons of television, 4 specials